Overwatch’s wide roster of fighters

Overwatch is a PC game that came out in 2016. It’s a first-person multiplayer team shooter online game, based in a futuristic sci-fi alternate earth setting. In this analysis, I will explore how space affects or is affected by the gameplay of Overwatch and how it is used to create a game world with its own lore, rules, and story.

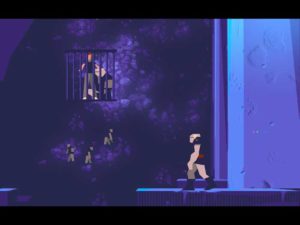

An alternate passageway in the Volskaya Industries map. Only flier characters can access it.

In every Overwatch game, the players choose from a diverse array of superhero-like characters and are divided into two teams who fight each other over an objective; escort a payload, protect or attack a zone, etc. The matches happen in a set of different maps based on real-life places; a Hollywood movie set, an oasis in Iraq, a city in Egypt, etc. The maps all share certain points in common; there’s a spawn area for each of the two teams, defensive zones where the players can take cover from attacks, and high platforms where the player can observe the game from afar. But they are all constructed differently; some have more high ground than others, some are contained in a building while others are in open space, and all of them have alternate passageways to the objective. Knowledge of how the maps are laid out gives the player many advantages. For example, knowing the location of health packs keeps you alive, and knowing where the secret routes are allow you to sneak up on the enemy team. As I became more familiar with the map, I found myself improving and winning more matches. Moreover, every character moves differently. Some are slower than others, some can fly, and others can use grappling hooks. The player can use this to their advantage, and some maps cater more to certain characters’ strengths than others. For example, the character Pharah has a jetpack which propels her to higher spaces that other players cannot access. Thus, open area maps with lots of high ground suit her well. Maps with long sightlines and windows are more suitable for sniper characters such as Widowmaker. A character with no movement abilities, such as the elderly Ana, cannot access many spaces of the same map. Thus, playstyles and the experience of any space varies depending on who the player plays as.

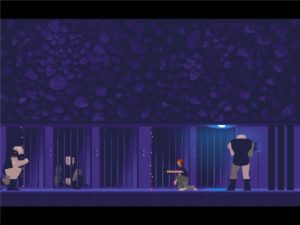

Blue lines enclose objective points.

One of Overwatch’s strengths is that it is easy to pick up. In addition to the levels’ architecture, there are design elements that make the goals clear to the player. For example, there are glowing blue arrows on the ground that lead the way to your current objective, red arrows line the enemies’ path. Lines that enclose contested areas change color depending on the stage of each game and which team is winning. Furthermore, green silhouettes show the location of your allies. Along with these design elements, the soundscape also changes to cater to player understanding of the current match. For example, voice lines signal the beginning and end of each match, as well as announcing when objectives are lost, won, or changed so that the player can quickly orient themselves as the match progresses. Other sounds that the player will note are footsteps – the most dangerous enemies have the loudest footsteps, and each of the 27 characters have unique footstep sounds. For example, hearing the loud jingling of spurs alert you to the highly dangerous McCree being nearby. However, the pacifist healer Mercy’s high heels make a hardly noticeable clack. Being attuned to these sounds and other graphical elements such as the shadows of ambushing enemies is crucial to winning, as well as making the game very beginning-friendly.

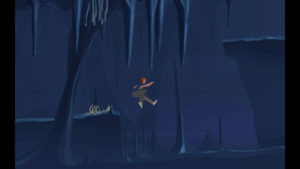

Table set for one at Château Guillard

Overwatch is interesting in the fact that most of the storyline and lore is established outside of the game, through short videos on Youtube, comics and biographies found on the Overwatch official website. However, knowing the whole story requires playing the game, as many of the in-game details, such as character interactions and the design of each map allow for a better, more immersive understanding of the Overwatch universe. During set-up time before matches, characters interact with each other through short voicelines. Some are comedic, some are heart-warming, such as the dialogue between Ana and her daughter Pharah, in which they warn each other to be careful. Others hint at the relationships that exist between characters, such as the hatred between former teammates Soldier 76 and Reaper. The attention to detail put in the environments as well is incredible and can tell a lot about the characters. One of the maps, Château Guillard, is a castle in France that we can infer from flags on the wall and the black widow spider on the window belongs to the French sniper Widowmaker. The single glass of wine placed on a crate in the darkened basement helps to illustrate the lonely, broken character of Widowmaker better than any sentence can. Another map in Egypt contains a small room stocked with Ana’s medical equipment and rifle ammunition. We can infer that this is where she hid during her time pretending to be dead. The maps are also prone to change according to holidays (Halloween or Christmas decorations) or in-game events: one of the maps was initially a normal airport in Western Africa, until it was attacked by a villain. This event is once again never shown in-game, but the damage caused to the area and signs of a fight – robots smashed against walls, debris, a broken glass case – allow players to make connections.

The attention to detail in game space makes Overwatch a highly immersive, beginner-friendly game with a memorable universe, unparalalled by any other game of its genre.